Welcome back, dear reader, to another installment on For The Love of Tunes! In this article, we will examine one of Maurice Ravel’s better-known works, Boléro. I’m sure that you’ve heard it before. It’s a relatively short work compared to some of Ravel’s other compositions, but it’s probably most known for its repetitive nature. The bones of the piece don’t change over much during the fifteen to seventeen minutes of performance time, and the only thing that allows the piece to grow are changes in orchestration, which build over time, leading to the well-known climax. Even the key barely changes throughout the work. Still, what was initially commissioned as a ballet has danced across numerous concert hall stages to become immediately recognizable to just about anyone.

Maurice Ravel’s Boléro is a masterwork that has echoed through the annals of classical music with its hypnotic rhythm and incremental build-up. However, behind the mesmerizing repetition and orchestral layering lies a poignant story of the composer’s struggle with his declining mental health.

A Little History

In the summer of 1928, the famous Russian dancer Ida Rubinstein asked Ravel for an orchestral transcription of six pieces from Isaac Albéniz’s set of piano pieces, Iberia. Work began soon after the request was made, but there was a problem. During the early stages of composition, Ravel learned that Spanish conductor Enrique Fernández Arbós had already orchestrated the movements and that copyright law prevented any other arrangement from being made. While Arbos was willing to waive the rights and allow Ravel to write his orchestrations, it was decided that the work would be taken in a different direction. Initially, Ravel considered orchestrating something from his library of compositions. Then he opted to write something completely new, based on the Spanish musical dance style known as the bolero.

The repetitive melody and the relentless rhythm create an almost trance-like effect, drawing listeners into the piece, anticipating each new instrument and marveling at how a simple theme can transform into a grand, exhilarating statement. The piece is famous for its dramatic crescendo, a hallmark that leaves audiences breathless. This gradual build to an explosive climax is both thrilling and satisfying, a testament to Ravel’s ability to manipulate musical tension and release.

Maurice Ravel himself described Boléro as “a piece for orchestra without music,” hinting at its mechanical nature. Yet, this repetition is precisely what makes it such a mesmerizing work. In a letter to his friend, Dimitri Calvoceressi, Ravel wrote the following of his latest work, “I am particularly desirous that there should be no misunderstanding about this work. It constitutes an experiment in a very special and limited direction and should not be suspected of aiming at achieving anything other or more than what it actually does. Before its first performance, I issued a warning to the effect that what I had written was a piece lasting seventeen minutes and consisting wholly of ‘orchestral tissue without music’ – of one very long crescendo. There are no contrasts, and there is practically no invention save the plan and manner of execution. The themes are altogether impersonal . . . folk tunes of the usual Spanish-Arabian kind, and (whatever may have been said to the contrary) the orchestral writing is simple and straightforward throughout, without the slightest bit of virtuosity . . . I have carried out exactly what I intended, and it is for the listeners to take it or leave it.”

It demonstrates Ravel’s innovative spirit and his ability to create profound beauty out of simplicity. Despite this, Boléro is imbued with a significant emotional depth. Ravel was aware of his declining abilities and expressed a mix of frustration and acceptance. He did not hold the new work in a very high opinion and remarked, “This is a piece which the big Sunday Concerts will never dare include in their programs.” In spite of Ravel’s struggles, Boléro stands as a hauntingly beautiful reflection of his inner world—a world where the music became a last refuge against the encroaching silence.

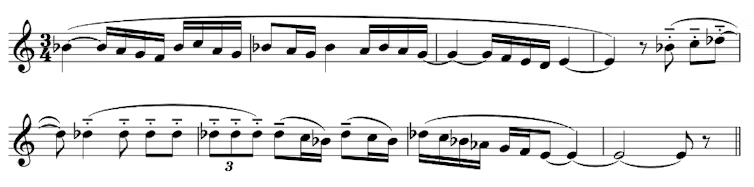

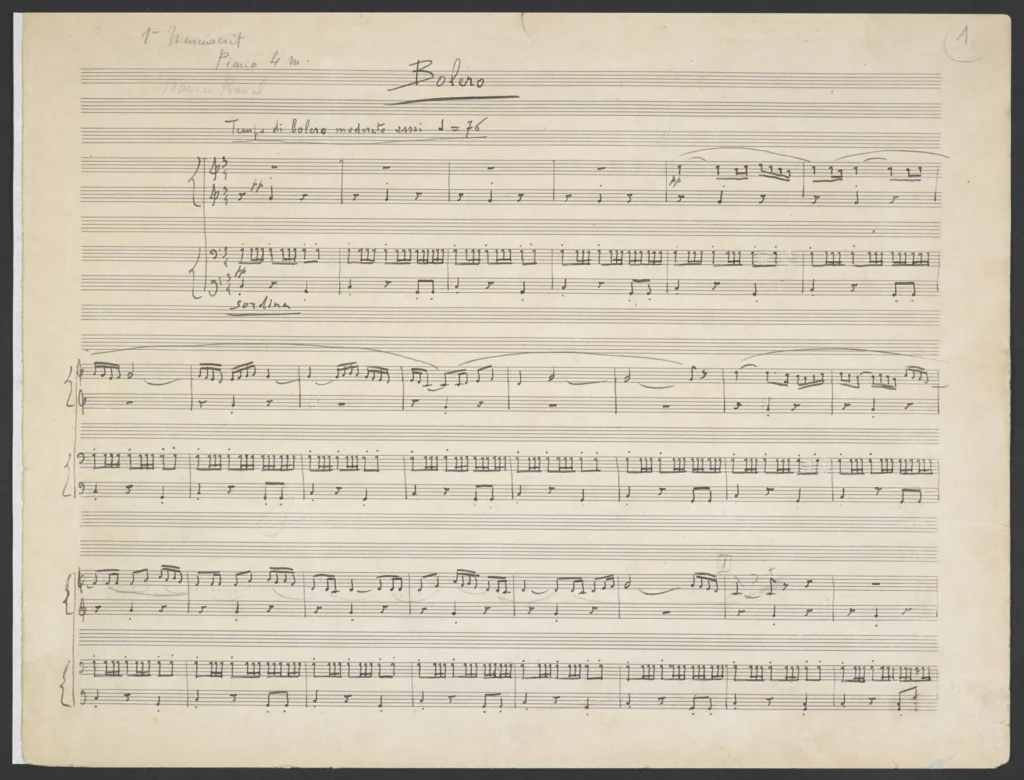

[Shown below] Snare Drum line (repeated approximately 170 times over the course of each performance):

The “insistent theme,” as Ravel called it:

The second melody that follows the first:

The genius of Boléro lies in its simplicity and meticulous orchestration. The piece begins with a single, insistent snare drum rhythm that continues unaltered throughout the composition. Over this unchanging ostinato, Ravel layers a memorable melody that is repeated, with each iteration introducing different instrumental colors and timbres. The melody, presented first by a solo flute, passes through various sections of the orchestra—clarinet, bassoon, oboe, and so forth—each time slightly reimagined by each instrument’s unique voice. As the piece progresses, the texture and volume grow, leading to an intense and climactic finale where the whole orchestra is brought into play.

Boléro emerged during rich musical experimentation in the early 20th century. While many composers of the time explored atonality and complex harmonic structures, Boléro is striking in its tonal simplicity and repetitive form. Despite—or perhaps because of—its unconventional approach, the piece quickly became a favorite among audiences and continues to be a staple in the concert hall.

Initially, some critics were divided about Boléro’s signature repetition. Some critics initially dismissed it as monotonous, but its unchanging rhythm and gradual orchestral layering captivated the public’s imagination, making it a regular feature in the orchestral repertoire. In fact, the piece’s popularity with audiences has never waned. Its usage in various films, commercials, and dance performances has cemented Boléro’s place in pop culture. It is often seen as a testament to Ravel’s orchestration and ability to create profound emotional impact via minimalist means.

It’s hard to mention Boléro without also mentioning the famous conductor, Arturo Toscanini. He gave the American premiere of the piece with the New York Philharmonic on November 14, 1929. The performance was met with “shouts and cheers from the audience, according to the New York Times, and it led one critic to observe, “It was Toscanini that launched the career of the Boléro.” He went on to state that Toscanini made Ravel “almost an American national hero.”

Today, Boléro continues to be celebrated not just as a musical composition but as a cultural icon. Its hypnotic rhythm and gradual crescendo have left an indelible mark on both classical and popular music, ensuring that Maurice Ravel’s masterpiece will resonate for generations to come.

By understanding the history and context behind Boléro, we gain a deeper appreciation of Ravel’s extraordinary ability to blend simplicity with complexity, creating a timeless work that continues to enchant and inspire. Maurice Ravel’s Boléro is more than a musical piece; it is a vivid portrayal of a composer grappling with the erosion of his mental faculties. The work offers a glimpse into Ravel’s mind—a mind that continued to create beauty even as it faced a dark and inevitable future. Appreciating Boléro is about recognizing its musical brilliance and acknowledging the exceptional courage of an artist confronting his own fragility with supreme grace. He retired soon after the premier in November of 1928, and despite his own dire predictions, Ravel’s Boléro proved to be a spectacular triumph—a truly remarkable “last bow” for a marvelous composer.

Recordings

As you know, dear reader, this is the part of the article that I enjoy most. Here are a few recordings I reviewed while writing this entry.

Pierre Boulez – Known for his precise and innovative interpretations, Boulez’s recording with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra stands out for its clarity and meticulous attention to detail.

Leonard Bernstein – This recording of Maurice Ravel’s Boléro with the New York Philharmonic is a remarkable interpretation that showcases Bernstein’s unique conducting style and the orchestra’s virtuosity. Initially released in 1965 on Columbia Records, this recording stands out for its dynamic energy and a remarkable level of restraint on the part of Bernstein.

Sir Simon Rattle – Rattle’s interpretation, performed by the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, is noted for its cleverness and other-worldly quality, making it a unique and captivating take on this piece.

Conclusion

My maternal grandfather’s favorite piece of orchestral music was Boléro, and it was fascinating to dig into its history. The discovery of Ravel’s struggles at the time he wrote the piece has certainly caused me to reconsider the work. If you are near Northwestern PA, on November 9th, 2024, the Erie Philharmonic will perform Boléro and a few other works. Thank you for reading!

You must be logged in to post a comment.